May 68 was one of the most important events of the current French Republic. Why was May 68 so decisive in the evolution of society?

This course on May 68 will help you better understand the stakes of this crisis, through the successive study of the following points

- Origin of May 68: the student revolution

- The extension by the workers’ crisis

- The generalization of the crisis

- Against May 68, the forces of order and the government react

- Consequences of May 68

- Slogans of May 68

If you prefer a brief summary, please refer to the sheet:

→ France guided by General de Gaulle (1944–1969)

Why May 68: the student revolution

I. The seeds of the events of May 68

The 1960s were first marked by a university explosion. In 1967, there were more than 500,000 students, 2.5 times more than seven years earlier.

On May 2, the University of Nanterre was closed. The students who were protesting there decided to meet at the Sorbonne.

On May 3, 1968, the courtyard of the Sorbonne was occupied by more than 400 demonstrators. The forceful evacuation of the police, normally forbidden in the university environment, provoked an escalation.

Prime Minister Pompidou left on May 2, and did not return until May 11. He then took measures of appeasement, decided to reopen the Sorbonne and to free the locked up demonstrators. But from then on the students demanded much more, and much more than these simple measures.

1. Student movements and unions

The UNEF (National Union of Students of France) lost importance between 1960 and 1965. From 100,000 members in 1960, they were only 30,000 to 50,000 members in 1965. The proportion went from one student out of 2 in 1960 to only one student out of 10 in 1965. Moreover, the UNEF was deprived of public subsidies in 1964.

The State preferred the National Federation of Students of France (FNEF), which had split from the UNEF in 1962 and was closer to the Gaullist government.

The March 22 Movement thus brought together several currents: the Revolutionary Communist Youth movement, the libertarian anarchists, the pro-Situationists*, the nerves and the unorganized, the latter representing half of the 142 occupants.

It is necessary to understand that the faculty of Nanterre, where these events begin, is situated in the outskirts of Paris, where there are no stores or almost no activities: no cinema, no restaurants, etc. The only place where the students meet is in the city center. The only place where the students meet is the cafeteria.

* The Situationist International, SI: This movement was born in 1957, after the criticism of the artistic forms of the time. The Situationist international then gained the political field, and questioned capitalism and bureaucracy. Two major works, published in 1967, mark this thought: Traité de savoir-vivre à l’usage des jeunes générations, by Raoul Vaneigem, and Société du spectacle by Guy Debord.

2. The revolutionary symbols of the ’60s

At that time, that is to say at the beginning of the sixties, anti-colonialism marked the minds, in particular of the students. This anticolonialism was transformed into anti-imperialism.

The war in Vietnam was an opportunity to protest against this imperialism. It was also the time of the emergence of international figures, symbolic of revolutionary commitment and new ideologies: Ho Chi Minh, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara.

3. The malaise of the students of the time

The PCF and the CGT were criticized by three movements: extreme left-wing groups, the Situationists and the Maoists.

The pamphlet De la mise en milieu étudiant, written in 1966 by members of the Situationist International, played a role in the political agitation of those years.

Gender relations were just beginning to become a political issue, to become a question for society.

According to the expression of the time, a “student malaise” was taking hold. It is also partly due to the reform of the universities. The students are in the middle of two laws, two university systems: a law until then selective, and a law of democratization. It is the access to the university which is in question.

The teenagers of the time identify themselves in new models of youth. The program Salut les copains and the film Pierrot le fou directed by Godard are examples of this.

II. The outbreak of the student crisis

1. The demonstrations, the 1st night of the barricades

During the months of May and June 1968, nearly 1100 demonstrations took place in only 43 days.

The modalities of the demonstrations varied greatly depending on the groups and the geographical conditions.

The first night of the barricades was the night following the demonstration of May 10. This demonstration had been called by the UNEF and the March 22 Movement.

Barricades were built on rue Gay-Lussac, but without having been ordered by the organizers of the demonstration. In fact, the organizational executives did not control the events.

These events were relayed by the media, in particular the radio cars of Europe 1 and RTL, contributing to the dramatization of the conflict, and to making it a national issue.

The repression against this movement took place until 5:30 a.m. Solidarity was then created between the demonstrators, public opinion and the workers’ unions.

The radicalization of the movement seemed to bear fruit, since George Pompidou, Prime Minister, gave in to the 3 demands of the demonstrators.

2. Occupations and action committees

The occupations of premises by the demonstrators began on May 11, 1968 at the Censier center. It was the Sorbonne’s turn on May 13 to be occupied, when it was reopened. At the Sorbonne, the occupation committee that took control of the premises was the object of struggles for influence among the various actors in the movement.

The action committees are improvised groups, as opposed to the bureaucracy. They are particularly numerous during May 68. The principles defended are sometimes of anarchist or Karl Marxist inspiration. Their fight is anti-authoritarian, for a direct democracy, against hierarchy and institutions.

The question in front of the multiplicity of these action committees is that of coordination. Is it necessary to coordinate the action committees? The Mouvement d’Action Universitaire, M.A.U., which is part of the first action committees of “May 3” is for coordination, which they are trying to implement from May 5. The March 22 Movement is opposed to it. It does not want to create again coordination from above.

3. Why the demonstrations?

The demands of the demonstrators concern almost all areas:

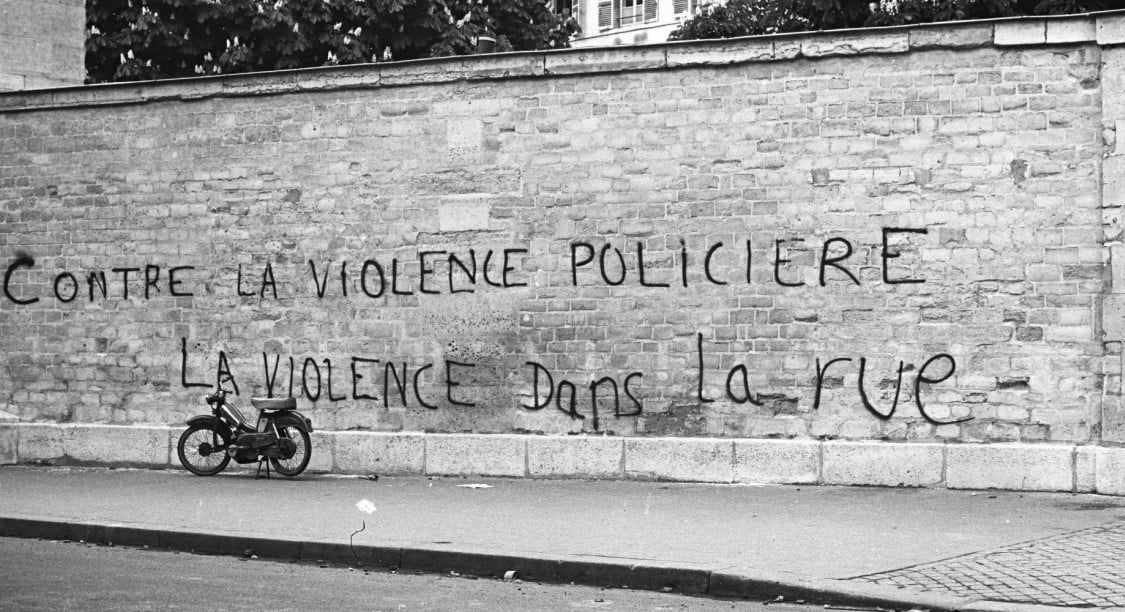

- To denounce the violence of the state that represses them

- To invent a critical and popular university

- To try to join the labor movement, striking professionals, and students

- Abolish the bureaucracy and hierarchical systems

- Denounce political and union maneuvers

- Criticize capitalism, consumerism, spectacle, alienation and exploitation

- To liberate creativity: this is a theme already before May 68, with the surrealists, and which finds an extension in the Culture and Creativity Commission of the March 22 Movement.

- To renew the forms of education

- To remove the bourgeois social frameworks

The extension by the workers’ crisis

In May a June 1968, there were more than 7 million strikers. However, what is one of the most important demonstrations of the century did not have a proportional place in the memories.

I. Continuity through revolution

1. Spontaneous movement?

Faced with the police repression of the 1st night of the barricades from May 10 to 11, the workers brought forward the strike they had planned to May 13. It is a success: 1 million strikers are claimed by the organizers (against 200,000 for the prefecture of police), the protest gains the professional circles.

The triggering of these strikes took three forms:

Either the strike was called by the union, or it was spontaneous but in favor of the unions, or the strike was spontaneous but also anti-union, which represents a minor case.

The actions that are remembered are those of factory occupations. However, this phenomenon was neither knew, nor was it in the majority in May 68.

2. Grenelle negotiations

The demands were as diverse as there were sites of mobilization. This is why, in order to deal with the question on a national level, it was necessary to nationalize these demands.

The radicalization of the crisis took place on the 22nd, when the students resumed demonstrations. On May 24, the second night of the barricades took place. On May 25, Prime Minister Pompidou opened negotiations at the Ministry of Social Affairs, rue de Grenelle. The choice of the ministry was not insignificant, it was to show that the issues were social and not political, and thus not to recall the demonstrations of 1936.

Several measures were taken, such as a 35% increase in the minimum wage, a 10% general wage increase in two stages, and measures in favor of general representation. However, the strikers refused these conclusions when they were presented to them on 27 May.

II. The plurality of factory situations

1. The particularities of each situation

For a part of the strikes, it was in fact a question of taking advantage of the general discontent, of the national conjecture, to obtain what they had not been able to obtain during the preceding conflicts. In fact, the local situations are relatively independent of each other.

This opposition between the general movement and the particularities of each situation is also found at the municipal, departmental and even regional levels.

The particularities are even found from one factory to another within the same firm. Renault’s Billancourt plant is a good example of this. Depending on the region, the factories do not have the same demands.

However, as far as the factories in the automobile sector were concerned, the demonstrations also followed the rhythm of May and June 1968, and were indeed at the heart of the strategies of the national players.

2. The workers are radicalized

Workers’ radicalism can be discovered through the prism of the strikes that took place at the Peugeot-Sochaux and Citroën-Javel sites.

During the resumption of activities after the war, in the case of Peugeot-Sochaux, numerous forms of violence and brutality were recorded, whether against strikers or non-strikers.

However, in these factories a majority of workers did not participate. They represent an important part of the workers, and therefore their behavior is difficult to predict. It is a population that followed the events from a distance, linked to more autonomy in their profession and to a lesser “usinization” according to Bourdieu’s expression: the massive recruitment that were carried out resulted in a lesser adherence of the recruits.

The new workers and the young workers weaken the authority of those in charge, and are more susceptible to political radicalization.

3. The partitions between social groups

There is no overlap between the workers and the unions. On the Renault-Flins site, everything is done to avoid union vitality.

May ’68 was also characterized by the mobilization of unlikely groups: conservative groups, but also groups with little industry.

The new actors of these events are the OS: specialized workers and the immigrants. Women workers also played a role in May and June 1968.

The article by George Marchais for L’Humanité, dated May 3, lent credence to the idea of a failed rendezvous between students and workers, that is, that they had not been able to unite their forces. This is, however, false on a finer scale, more local, where we observe that the meeting did take place.

May Sixty-eight also had the effect of accelerating the loosening of social partitions.

The insubordination of the new workers, the young workers, is linked to a double evolution: the previous mutation of the school, and the transformation of the worker recruitment induced by the industrial decentralization.

The generalization of the crisis – Summary May 68

The criticism emanating from May 68 carries both an anti-authoritarian spirit, and protests against the vertical division of labor as well as the horizontal social division.

I. The artistic professions

The writers are in the avant-garde. The hierarchies are shaken there.

As for architects, the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts was a hotbed of protest. The Malraux decree of December 6, 1968, put an end to the single Parisian school that controlled the regional schools.

The occupation of the Odéon theater took place on May 15, 1968, which remained an untouchable symbol. The link between theater and politics is rethought, the places serve the political cause, and the foundations of cultural decentralization are questioned. The Declaration of Villeurbanne protests against the illusion and mystification of cultural democratization: illusion because there remains a “non-audience”, and mystification because only classical texts are performed, which contributes to bourgeois culture.

II. The authorities and religion

The magistrates are concerned by the criticism and the crises of reproduction. The union of the magistracy is created on June 8, 1968. It is a question for this union of alerting on the social effects of the projects of laws, while weaving links with the workers’ centers. Ideas against hierarchy and bureaucracy were conveyed. It is also in these trades the meeting between two generations.

The contestation also targeted the hierarchical distribution of medical knowledge and the social division of health care work, represented by the opposition between nurses-technicians-auxiliaries and learned doctors. These two criticisms were led by the Centre national des jeunes medicines, created in 1964, and the Comité d’action de santé.

The criticism also concerned the health structure: the population would be kept in a state of work only to produce and consume.

As far as religion was concerned, Christians only participated in a limited and minor way in May ’68. However, the weight of the Christians involved in May 68 is more important within the Church itself. Until May 21, 1968, it was a question of evangelical justification of the duty to act. On May 21, 1968, an “appeal to Christians” was published in Témoignage Chrétien, which was signed by numerous protagonists.

The changes demanded by May 1968 were carried more by young Christian protestors and young seminarians. They questioned the hierarchical links within the Church. The bishop of Paris, Mgr Marty, had this formula “God is not conservative”, which, given the implications that could be drawn from it, was the talk of the town at that time. The new breath of May 68 is analyzed in the continuity of the aggiornamento of Vatican II.

III. The “laughter of May” (expression of Pierre Bourdieu)

May Sixty-eight is the occasion for several categories of people to make their voice heard. It is, first of all, the case of the General Union of the Blind and Greatly Disabled, and more generally of the sick; it is then the case of the immigrants. Michel de Certeau said of May 68: “We took the floor as we took the Bastille in 1789.”

May Sixty-eight is also a general uprising against the finitude of the social world. The movement questions several relations: legitimate/illegitimate, normal/deviant, possible/impossible, rulers/governed. In this last relation, it is all the relations of domination which are also played: trade-union leaders/workers, decision-makers/executors, creators/consumers, etc.

For K. Ross, it is an “escape from the determinations imposed by society”.

Equality is a value erected against authority. This equality is reflected in the right to speak granted to everyone in the action committees, in the non-confrontational meeting between students and workers, in the relationship of the sick with the non-sick, of the profane with the good Christians.

Against May 68, the forces of order and the government reacted

I. Maintaining order

Before May ’68, the forces of order were provided with new weapons in the context of the repression against the communists in the 1950s, then against the OAS in the early 1960s. Police savagery risks reviving the memory of the Charonne metro tragedy.

However, police violence is relative, even weak in comparison to what happened during the Algerian war: the objective is to put distance between people, to avoid hand-to-hand combat.

The slippage that occurred was never the result of instructions, of a coordinated intention, but of the police officers’ loosening of their hierarchical ties.

It is then difficult to control the multiplicity of forces on the ground, which are composed of several state bodies, not only the police. The government even pretended in May 1968 to envisage the intervention of the army.

The vagueness at the top of the State did not help the resolution of the conflict and the action of the forces. There were two opposing strategies: that of Prime Minister Pompidou, who favored a peaceful depoliticization of the conflict. And that of General de Gaulle, who wanted to politicize the crisis and get out of it by emphasizing the charisma of the president.

It is not so much this vagueness that complicates the control of the demonstrations, but especially its publicity, that is to say when the public becomes aware of these divergences at the highest level of the State. The prefect of police noted that he received few if any instructions between May 2 and 11.

II. Supporters

Supporters also organized themselves in favor of the government.

The extreme right organized parades and meetings in Paris.

The committees for the Defense of the Republic, created for the occasion, wanted to support the presidential action, while the counter-revolution also gathered around the Gaullist Jacques Baumel.

There was also the mobilization of the FNEF, a rival of the UNEF. The intellectuals of the right were committed to the government.

The latter prepared a rhetorical line of defense, and drew parallels between the May ’68 movement and the memory of the Occupation, as well as with the civil war.

On May 30, de Gaulle announced the dissolution of the National Assembly. A big demonstration was organized on May 30, 1968: about 400,000 people marched in Paris. Eighty-three other demonstrations took place in the other departments in three days.

The media was an important part of this reaction. On May 23, the peripheral radio stations were deprived of the right to use the frequencies that had been allocated to them.

At that time, France had 8 million television sets. This shows the importance of the ORTF, which covered the events of May 68, but in a very biased way, in favor of the government.

It is for these problems of objectivity that a strike is organized in the personnel on May 17, and another of the journalists on May 25, which both fail in the end.

III. The Left

The FGDS, Federation of the democratic and socialist left, gathers at the same time the SFIO, the radical party and the Convention of the republican institutions. However the FGDS is always in shifts during this crisis of May 68. It is not rare that it is counted as one of the bourgeois auxiliaries.

In this respect, François Mitterrand, one year after the events, analyzed the ideology of the student leaders as “learned Poujade”.

The SFIO came closer to legalism, while the CIR developed interested links with the student movement. The relations with the PCF are those of associates but rivals at the same time.

François Mitterrand tried to capture the discontent for his own benefit, but it was a failure: at the end of June 1968, the FGDS had lost half of its voters.

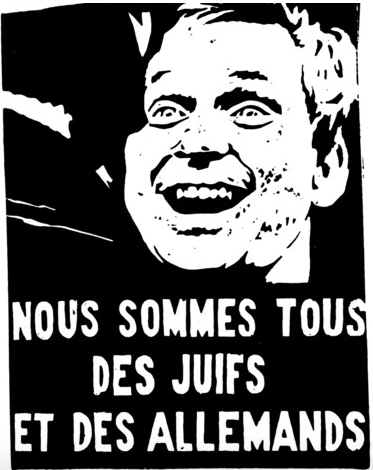

The PCF tried as best it could to control the movement, which developed without its impetus. While Georges Marchais denounced on May 3 “the German anarchist Cohn-Bendit” and the “false revolutionaries”, on May 7 the PCF recognized the “legitimacy of the student movement”.

In fact, the PCF seeks throughout the crisis of May 68 to keep a minimal link with the movement, while reducing its scope and impact. These political hesitations are not without causing contestations within the PCF itself on the conduct to hold.

Consequences of May 68

I. The return to the political game

The presidential charisma, embodied by de Gaulle, was transformed after May 68 into partisan Gaullism. The prestige of the presidential person has lost its luster.

Pompidou, on the occasion of the crisis of May 68, became more important than de Gaulle. He returned on May 12, and gave a speech that was welcomed on May 14 in the National Assembly,

There are then several interpretations to understand the disappearance of de Gaulle in Baden-Baden on May 29 whether to check his military support, or to withdraw from political life.

De Gaulle did not like the rise of Pompidou, and replaced him with Couve de Murville. The April 1969 referendum on the reform of the regions and the transformation of the Senate, in which the “no” vote was victorious, led to de Gaulle’s withdrawal.

II. The analysis of May 68

May 68 is analyzed by Bourdieu as a suspension of the adhesion to the established order. The discovery of the arbitrariness, which founded the established order, provokes an unprecedented moment, where the men become aware of this arbitrariness and decide to leave it, or at least to suspend it.

Deleuze and Guattari write as for them that “May 68 did not take place”, that is to say that “the French society showed a radical impotence to operate a subjective reconversion at the collective level, such as 68 required it”.

If May 68 was indeed this moment where the arbitrary had been contested, then the failure of May 68, its repression, would be to understand as the return to the dose, that is to say a return to the established order, without questioning.

In an interview published in 1988*, Cohn-Bendit analyzed May ’68 in these terms: “In its form, it is the first modern movement of advanced industrial societies and in its expression, it is the last revolutionary revolt of the past. The two aspects are mixed. I believe that 1968 fundamentally announced all revolts that push towards autonomy, the civil society of individuals, and the complete transformation of society!”

Asked about the results of May ’68, he adds, “It is, for example, the Catholics who do not listen to the Pope when he talks about contraception,” and about what remains of May ’68: “what May ’68 has generated: the environmental movement, the women’s movement, the anti-totalitarian sensibility”.

* Dreyfus-Armand Geneviève, Cohn-Bendit, Daniel. The movement of March 22. Interview with Daniel Cohn-Bendit. In: Materials for the history of our time. 1988, N. 11–13. Mai-68: Les mouvements étudiants en France et dans le monde. pp. 124-129.

Slogans from May 68

→ 50 historical quotes in the 20th century

- Subway, work, sleep.

- We do not want a world where the certainty of not dying of hunger is exchanged for the risk of dying of boredom.

- Elections, an asshole trap.

- Imagine.

- It is forbidden to forbid.

- Boredom is counter-revolutionary.

- Imagination takes power!

- No to the police state!

- Even if God existed, he should be suppressed.

- ORTF : The police speak to you every evening at 8 p.m.

- We buy your happiness. Still it.

- Everything is political.

- Take your desires for reality.

- Be realistic, ask for the impossible.

→ Contemporary History Cards

(The photo on the front page of this article, taken by Gilles Caron on May 27, 1968, shows Pierre Mendès France in the middle of the crowd.)

A beautiful nonsense May 68; inflation would claw back the wage increases with two throws of the dice.

Please I want to know how my uncle Mouhamed souli studying at the serbonne in the 60s (1960) died? Of Tunisian origin Mohamed Ben Hannachi Souli